Exhausting a Crowd by Kyle McDonald

What is the overarching area of research?

I will research participatory internet art and design a speculative interactive online art project.

What are the key questions or queries you will address?

- How can online participatory art create social structures between people?

- What are the (para)social and interpersonal dynamics of these relations?

- How do internet technology and interfaces facilitate and influence this?

Why are you motivated to undertake this project?

I’ve long been fascinated by participatory online art and the communities they create. I investigated interactive performance in last term’s group project, but I’d like to see what changes when it goes online. Participatory internet art is a relatively new medium; it’s becoming more prominent now due to improved internet technology. These kinds of projects may not be framed as art, so academic analysis is lacking. I’d like to analyze this medium through theoretical frameworks, particularly interactive art, performance art, and game studies.

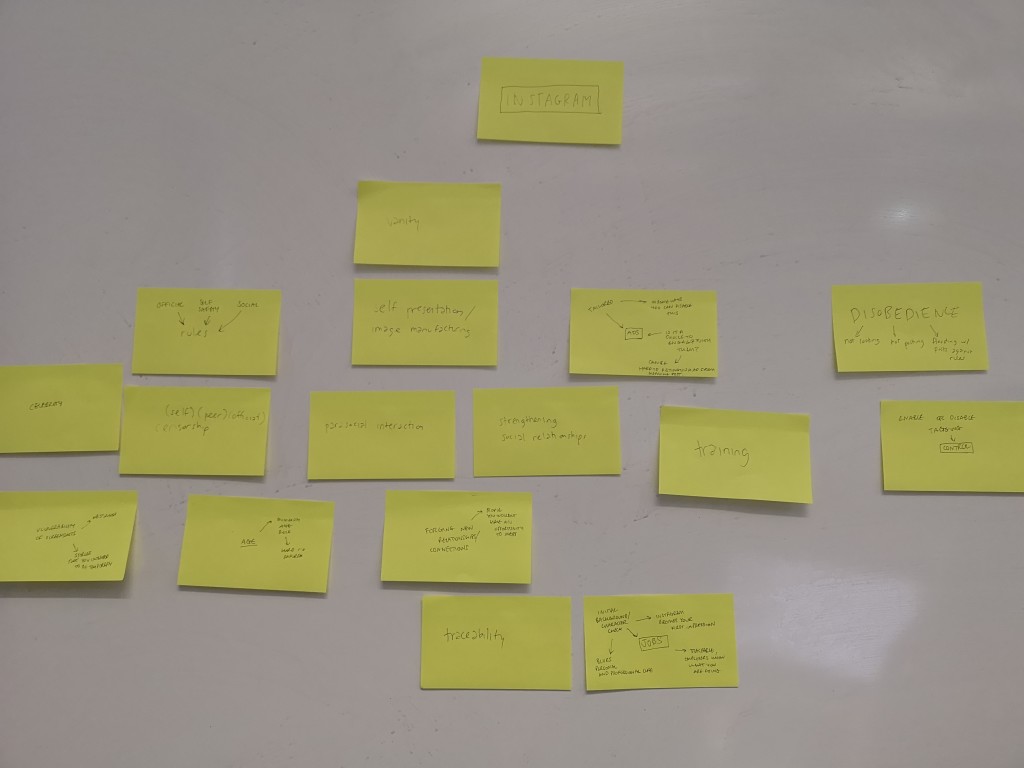

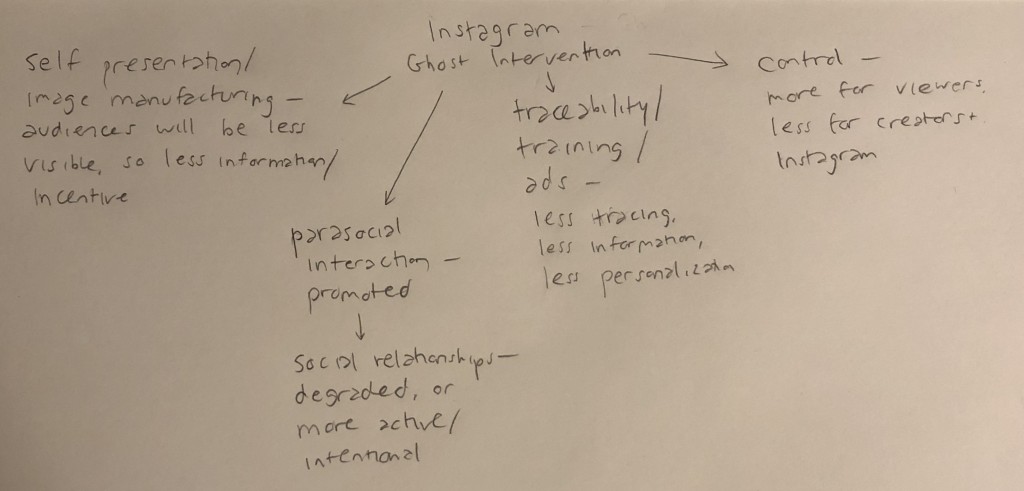

Examples of participatory online art projects:

- “Twitch Plays Pokemon,” where a chat controls a Pokemon game through text commands

- “Take Care of My Plant” by Tyler Jay Wood, where a plant waters itself based on daily community vote

- Ice Poseidon’s Twitch channel by Paul Denino, where he livestreams his life and viewers influence it to extreme lengths

- “Exhausting a Crowd” by Kyle McDonald, where online viewers comment on people in a livestream of a crowd

- “Die With Me” by Dries Depoorter and David Surprenant, a mobile chat room that users can only join if their battery is less than 5%

For the practice component, I’ve never designed an online participatory project and I’m excited to explore a new medium. I’m interested in transposing the interpersonal complexity of performance and interactive art onto a networked space. I’d like to fully explore the social and emotional possibilities of this medium.

I’m choosing to design a speculative project because this assignment focuses on theoretical rather than technical achievement. Also, participatory online artworks can require a lot of complex technology, and it’s difficult and uncertain to get players to interact. I’d like to take advantage of the speculative nature of this project to design at a large, ambitious scale. Depending on the outcome, I may realize the project in the future.

What theoretical frameworks will you use in your work to guide you?

- Interactive and participatory art

- Performance art

- Game studies

- Internet and network studies

What theoretical frameworks will you use in the analysis of your project?

- Interaction design

- Speculative design

How will you document your project?

In my paper, I will write analyses of a few participatory internet art projects. I will also explain the reasoning and design process behind my own speculative project.

I will develop a front-end web prototype that simulates my participatory art project. The user should be able to interact with it as though they were really participating.

I’ll also write descriptions and diagrams of how the back-end technology should work. Finally, I’ll write about the ideal participatory outcomes of the project.

Timeline for project milestones

- March 4: Select texts

- March 18: Read texts

- March 25: Annotated bibliography

- March 25: Select interactive online artworks to analyze

- April 1: Develop idea for participatory online project

- April 15: Design participatory online project

- April 29: Develop web prototype

- May 13: Write paper

- May 13: Post to blog

Budget

Annotated Bibliography

Burrough, Xtine, editor. Net Works: Case Studies in Web Art and Design. London: Routledge, 2011.

Net Works provides case studies of internet art projects, grouped into themes. The chapter particularly relevant to my project is “Crowdsourcing and Participation.” Burrough herself designs participatory projects for networked publics. She analyzes one of her own projects, “Mechanical Olympics.” This chapter presents a theoretical discussion of crowdsourcing, though it focuses more on labor than social relationships. The chapter also provides a history of developments in online communication, and how that influenced net art.

In their chapter “Google Maps Road Trip” from the same section, Peter Baldes and Marc Horowitz describe their project which involves livestreaming and a chat room. This provides insight into how participatory online art facilitates interpersonal relationships.

Other relevant chapters to my project are “Communities,” “Surveillance,” and “Performance.” In the “Surveillance” section, Lee Walton writes about his project “F’Book,” which uses existing tools (Facebook) to subvert his social community. In the section “Performance,” Jonah Brucker-Cohen describes his participatory artwork “Alerting Infrastructure,” where online viewers affect the physical destruction of a building. The text delves into how the bidirectional relationship operates between viewer and artwork.

The book is structured as artists describing their own artworks. This provides a valuable insider perspective of the artists’ intentions, technical development, and conclusions. However, these perspectives may lack objectivity. Because the book only focuses on specific artworks, its scope is limited. The tone is for the casual reader rather than academic. I found that there wasn’t enough analysis of audience behavior. The book was written in 2011, and the technologies and internet it describes are already slightly dated.

Isbister, Katherine. How Games Move Us: Emotion By Design. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2016.

Isbister writes from the discipline of game studies. In her chapter “Social Play,” she presents a sociological approach to game design, where developers create social situations for players to interact together. She introduces three building blocks for social digital games: coordinated action, role play, and social situations. All of these are applicable not only to games but more broadly to interactive art.

While Isbister writes about interactive games, she also brings the theoretical framework to online play. In her chapter “Bridging Distance to Create Intimacy and Connection,” Isbister examines how networked games can create “connection, empathy, and closeness” through “asynchronous mass play.” She covers several ways game designers can foster networked relationships through “powerful minimalist tools for coordinated action and communication.” She also describes how multiplayer networked games can create communities organizing for collective action. I’ve seen similar communities emerge around interactive online art projects.

Though I believe game design is a useful framework for looking at interactive art, it can be limiting. Isbister’s case studies only encompass established games like Words With Friends and Journey, rather than interactive art projects. Moreover, the interactions she describes between players are mostly positive moments of closeness and connection. I’d like to explore more complex relationships that this medium can facilitate.

Kwastek, Katja. Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2013.

In Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art, Kwastek presents a theory about the aesthetics of interaction, which focuses on “describing and analyzing the actions and the processes of perception and knowledge acquisition that are made possible through engagement with interactive media art.”

Kwastek begins by offering historical context for interactive digital art. She writes about performance art, social sculpture, and games, and describes how principles used there are precursors to contemporary interactive art. She outlines how the internet enables telepresence and remote control, and how art can use these capabilities.

In the chapter “The Aesthetics of Play,” Kwastek outlines the theoretical principles of both play and performance. In the next, “The Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art,” she breaks down interactive art into components of actors, space, time, and interactivity. The modular nature of these principles makes it easy for me to apply to analyzing other interactive artworks.

Finally, Kwastek presents case studies from interactive artworks. She focuses less on internet art and more on physical spaces. In the internet artworks she covers, “Agatha Appears” by Olia Lialina and “Bubble Bath” by Susanne Berkenheger, the viewer’s role is mostly as an observer. However, Kwastek also writes about how Sonia Cillari uses the “performer as interface” in her physical performance “Se Mi Sei Vicino.” I can apply those ideas towards my own analyses of performative internet art.

This book is a valuable theoretical grounding for my project. I can analyze existing participatory internet art projects as well as develop my own with Kwastek’s framework.

Reference list

Burrough, Xtine, editor. Net Works: Case Studies in Web Art and Design. London: Routledge, 2011.

Candy, Linda and Sam Ferguson, editors. Interactive Experience in the Digital Age: Evaluating New Art Practice. Nottingham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 2014.

Greene, Rachel. Internet Art. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2004.

Himmelsbach, Sabine, editor. Gateways: Art and Networked Culture. Berlin: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011.

Hope, Cat and John Ryan. Digital Arts: An Introduction to New Media. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Isbister, Katherine. How Games Move Us: Emotion By Design. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2016.

Kholeif, Omar, editor. You Are Here: Art After the Internet. Manchester: Cornerhouse Publications, 2014.

Kwastek, Katja. Aesthetics of Interaction in Digital Art. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2013.

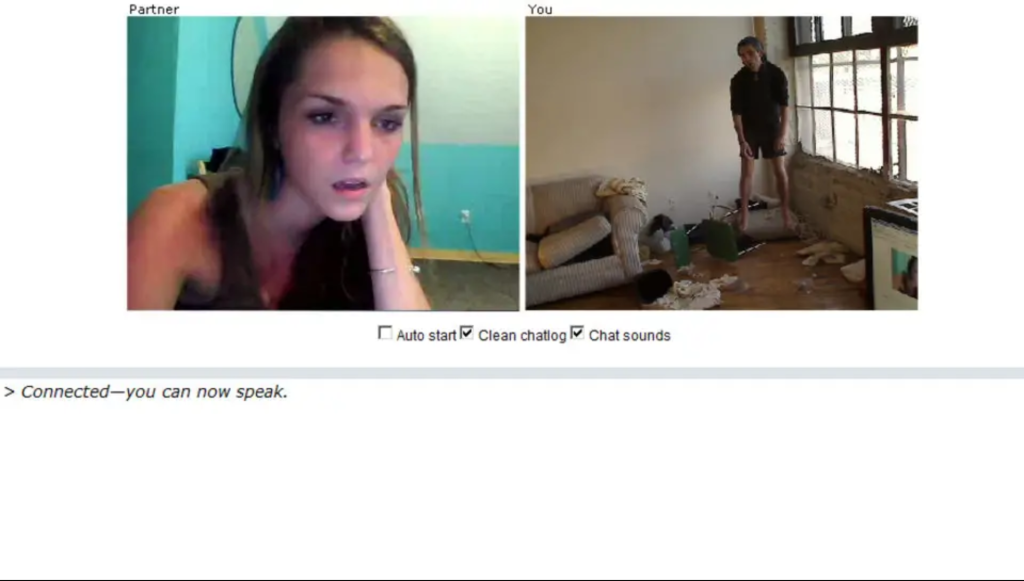

No Fun by Eva and Franco Mattes

No Fun by Eva and Franco Mattes

Ice Poseidon

Ice Poseidon

Human Sensor by Kasia Molga

Human Sensor by Kasia Molga

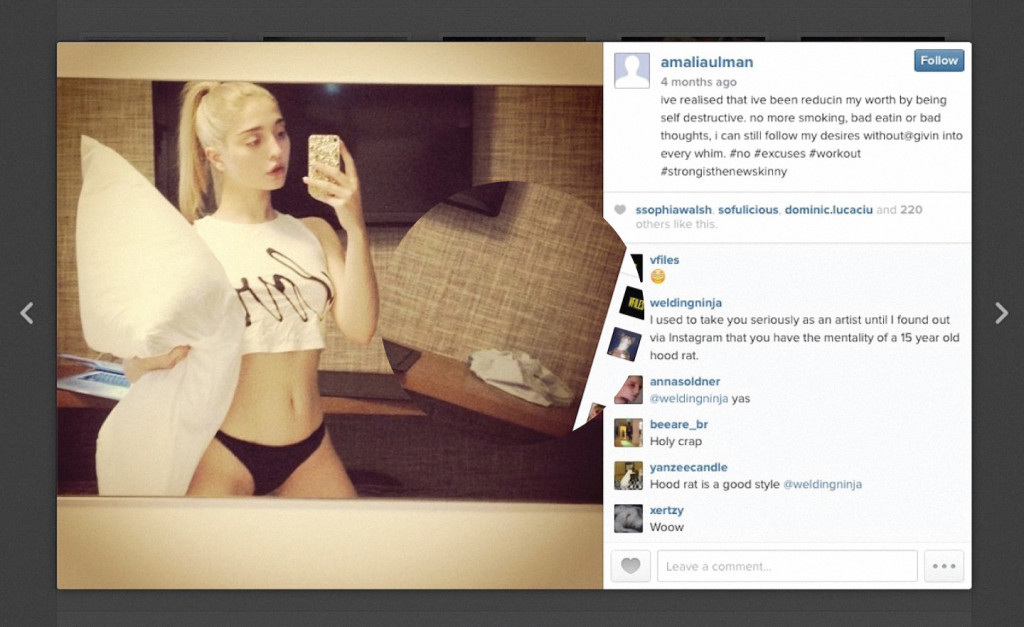

Excellences and Perfections by Amalia Ulman

Excellences and Perfections by Amalia Ulman