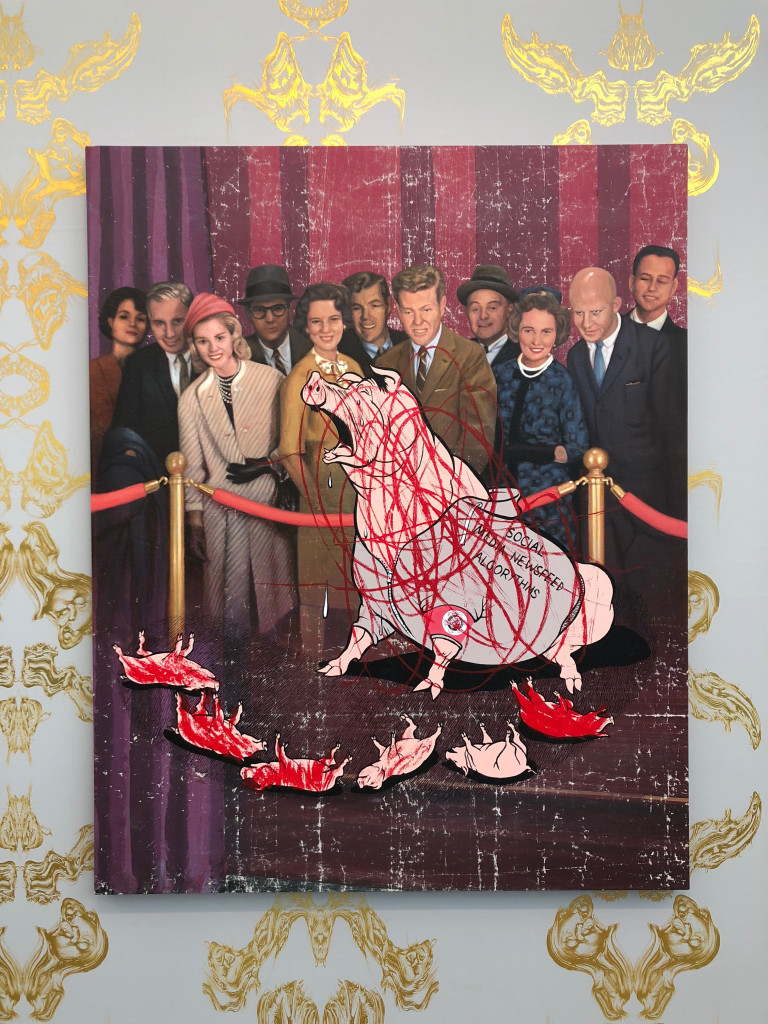

“The algorithm” has become a meme at this point. At the Frieze Art Fair, I saw this painting by Jim Shaw, depicting a crowd surrounding a yowling pig with “Social Media Newsfeed Algorythms” written on its back.

The whole exhibition had the context of being against Trump, a president known for his (mis)use of social media. Still, seeing this the same week that I read Tarleton Gillespie’s essay “Algorithm [draft] [#digitalkeywords]”, I thought about how the concept of the algorithm has pervaded even the arts. It’s been reduced to a singular entity. Gillespie writes:

“Algorithm” may in fact serve as an abbreviation for the sociotechnical assemblage that includes algorithm, model, target goal, data, training data, application, hardware — and connect it all to a broader social endeavor.

In the arts, where people comment on social issues but may not necessarily have a technical background, the algorithm is a synecdoche. It’s an authority, like Trump, but also an object to be stared at, mocked, and scribbled out. It is Facebook, meaning the actors behind Facebook, but also a technological process out of our direct control.

I researched the Facebook newsfeed algorithm for this assignment. I came across articles from Hootsuite geared toward helping marketers spread their content. The algorithm is constantly changing, which keeps marketers on their toes as they respond with new strategies. In the most recent change, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook would prioritize content from “friends, family and groups.” Hootsuite writes:

The new algorithm prioritizes active interactions like commenting and sharing over likes and click-throughs (passive interactions)—the idea being that actions requiring more effort on the part of the user are of higher quality and thus more meaningful.

It struck me that what Facebook said about their algorithm is a form of marketing – to make the company seem like it rewards “meaningful” interactions for the good of its users. The algorithm’s exact process is always hidden, leaving people to guess at it. Peoples’ livelihoods depend on it, i.e. if a company is promoting a brand, or a person is simply trying to maintain social connections. Hence, the algorithm becomes something powerful yet unknowable.

In a way, we are all conducting software studies experiments on our Facebook newsfeeds. Whether consciously or not, every action we perform (like, comment, even look) will influence our result of the algorithm.

One actual experiment I “liked” was Mat Honan’s article for Wired, where he liked everything he saw on Facebook for two days. He reported that at the end, his “feed was almost completely devoid of human content” as well as politically polarized, extreme on the left and right.

I would extend this experiment by reporting on how it felt emotionally for a user to interact with the algorithm. Personally, I would be mortified to publicly “like” something I disagree with, or something sensitive like bad news from a friend. I would be interested in studying how people feel interacting with the algorithm in routine ways – do they feel empowered? Disempowered? Do they know how the algorithm works? Gillespie’s article was all theory, though some of it rang true to me. From what I’ve seen, software studies about algorithms doesn’t dig in to how it makes its users feel. I would like to explore the intersection of algorithm and human emotion further.

References

Gillespie, Tarleton. “Algorithm [draft][# digitalkeyword].” Culture Digitally, 25 Jun. 2014. http://culturedigitally.org/2014/06/algorithm-draft-digitalkeyword/.

Honan, Mat. “I Liked Everything I Saw on Facebook for Two Days. Here’s What It Did to Me.” Wired, 11 Aug. 2014. https://www.wired.com/2014/08/i-liked-everything-i-saw-on-facebook-for-two-days-heres-what-it-did-to-me/.

Tien, Shannon. “How the Facebook Algorithm Works and How to Make it Work for You.” Hootsuite, 25 Apr. 2018. https://blog.hootsuite.com/facebook-algorithm/.